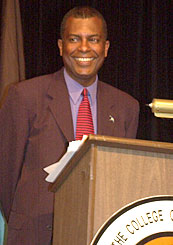

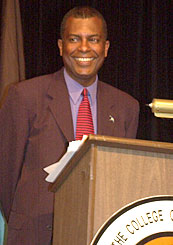

THE SIR

LYNDEN O. PINDLING DISTINGUISHED LECTURE

BY THE HON. FRED MITCHELL B.A., M.P.A., LL B

MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS & THE PUBLIC SERVICE

DUNDAS CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS

NASSAU, THE BAHAMAS

BIS Photos by Peter Ramsay

Monday 5th May 2003

“What it means to be Bahamian”

I wish to say at the outset what an honour it is for me to have been asked

to deliver this distinguished lecture. I express my thanks to the

Sir Lynden O. Pindling Foundation in particular the widow of Sir Lynden,

Lady Marguerite Pindling. I wish also to thank the Chairman, Council

and President of the College of The Bahamas for this opportunity.

I would like in particular to thank my friend Felix Bethel, now a lecturer

in politics at the College of The Bahamas and head of the Social Science

Division of the College. We have both come a long way since those

days when we used to share in the purchase price of the Sunday New York

Times, almost thirty years ago.

I wish to say at the outset what an honour it is for me to have been asked

to deliver this distinguished lecture. I express my thanks to the

Sir Lynden O. Pindling Foundation in particular the widow of Sir Lynden,

Lady Marguerite Pindling. I wish also to thank the Chairman, Council

and President of the College of The Bahamas for this opportunity.

I would like in particular to thank my friend Felix Bethel, now a lecturer

in politics at the College of The Bahamas and head of the Social Science

Division of the College. We have both come a long way since those

days when we used to share in the purchase price of the Sunday New York

Times, almost thirty years ago.

I need to say that this lecture affords me the third

draft for a book that I am producing to mark my 50th birthday that I will

celebrate on 5th October this year. I had hoped to do a lecture tour

around the country to mark this my 50th year and to present various aspects

of my life as I have seen them. The first installment can be seen

on the World Wide Web. It was written shortly after the death of

Sir Lynden Pindling in 2000 and delivered at the College of The Bahamas

in September 2000. It can be found on the website fredmitchelluncensored.com

and is called ‘Pindling and Me’.

The second segment is unpublished and undelivered but

I hope to get a venue soon. Today’s notes will form the third of

these drafts.

I also want to say that in many cases, I am speaking

frankly about events that are of extreme sensitivity to many Bahamians.

These remarks may be controversial in some quarters. But this is

a College of The Bahamas forum and so I say these things in an academic

setting and they should be accepted in that light. This is not public

policy of The Bahamas, and one hopes that my address is discussed in that

light. And I hope that what I say here is respected in the light

of a frank discussion on the subject and not as some kind of political

fodder. I do not pretend that the analysis is scientific. It

is clearly impressionistic but I think nevertheless instructive.

In 1972, a man named Robert Keen who was the public

relations representative for the Bahamas Government arranged with my then

boss the late William Kalis for me to spend one academic year in London

working at the agency Infoplan Ltd. while I attended a special programme

of Antioch College, my then university at the University of London.

I arrived in London in 1972 shortly after the General Elections of September

were held in The Bahamas that decided the issue of independence. I joined

my flat mates Anthony Kikivarakis, David and Allan Pinder in a small flat

in north London in Woodgreen at 47 Granville Road.

One of my first jobs at Infoplan was to proof read

the White Paper on Independence for The Bahamas. In it was the blue

print of the then Progressive Liberal Party government, headed by Sir Lynden

Pindling for the country’s future. My contribution to the effort

was to change all the spelling of the words that ended in “i-z-e” to the

spelling “i-s-e”.. I was proud of that job and felt when I was doing

it that one day I would get to repeat that story to a forum such as this.

The Hon. Darrell Rolle was then the Minister for Transport and one of the

members of the delegation negotiating the Independence of The Bahamas with

the British. Somehow during the talks, I met up with Mr. Rolle

and happened to take a taxi ride with him to a train station from the Dorchester

Hotel while he went on to Lancaster House where the talks were coming to

an end. I remember him saying to me that the Government had put forward

a proposal that would effectively prevent the children of illegal immigrants

from claiming the citizenship of the new state to be known as the Commonwealth

of The Bahamas.

The Hon. Darrell Rolle was then the Minister for Transport and one of the

members of the delegation negotiating the Independence of The Bahamas with

the British. Somehow during the talks, I met up with Mr. Rolle

and happened to take a taxi ride with him to a train station from the Dorchester

Hotel while he went on to Lancaster House where the talks were coming to

an end. I remember him saying to me that the Government had put forward

a proposal that would effectively prevent the children of illegal immigrants

from claiming the citizenship of the new state to be known as the Commonwealth

of The Bahamas.

That meant that in fulfilling the words of the white

paper that citizenship was the most important issue, the Government had

decided and the Opposition at the time agreed that citizenship of The Bahamas

would be defined more narrowly than the concept had been understood up

to July 10 1973. Now birth alone was no longer going to be the criterion

for citizenship of The Bahamas. With the coming of the new constitution

citizenship would be defined as birth, plus ancestry. In other words,

you had to have Bahamian ancestry in order to claim Bahamian citizenship.

That ancestry had to come through the father, if you were married to the

mother of the child and through the mother if the child was born to a single

woman. This changed the formulation that existed before 1973 where

if you were born in The Bahamas you were a citizen of the United Kingdom

and Colonies at birth. And all those who were in that category at

Independence Day were qualified for the new citizenship of The Bahamas.

It seemed like a good idea at the time, but few

people would have predicted the absolute public policy nightmare that the

definition created. On a practical level, many have argued that today,

we have thousands of cases of persons who were born in the country to illegal

immigrants, who have known no other country but unless they apply before

their nineteenth birthdays, they have no claim or entitlement to Bahamian

citizenship. And in the meantime we have neither the capacity nor

the willingness to expel them or their parents from the country.

And further some of our social scientists and economists are arguing that

we risk the collapse of our economy if we do expel them from the country.

And so we have many, many cases today where families

are divided by the definition. For example, a family of foreign persons

had five children, three born before independence and two afterwards.

The children born before to the same parents and in the same circumstances

are Bahamians, but the two who were born after independence to the same

parents and in the same circumstances are not.

It is also interesting to note that many of the

leaders who defined what a Bahamian is in legal terms , would not have

been Bahamian citizens, if you accept the theory of citizenship and domicile

current in 1973 as passing through the male line and take out the factor

of marriage. And it is also curious that the concept of what is Bahamian

was defined by persons in the Government who had themselves at least one

foreign parent, and so in a sense were first generation Bahamians.

And so it is curious to me that the concept legally

of who is a Bahamian is certainly a recent concept in that it is just about

30 years old. But that legal definition actually differs not only

from the qualifying legal concept before Independence but also from what

was considered Bahamian in the social and cultural sense and in our common

understanding both prior to and after independence. What we commonly

understand to be Bahamian in the cultural and social sense is someone born

and raised in The Bahamas.

It can be argued that the new legal definition has

in fact made it harder not easier to deal with the question of who belongs

to The Bahamas. And it is a difficult public policy problem to solve

because of the emotional sensitivity of the subject, and the fact that

many Bahamians, however defined, want to expel the Haitian immigrants and

their children born here from The Bahamas and send them back ‘home’.

The singer Smokey 007 used to sing a song with the

chorus: ‘You born there! You born there!’ And if you listen

to the words of the song, it is clear that the popular definition of Bahamian

is simply someone born in The Bahamas. But that of course does not

wash with the law. And it creates hard public policy.

About

three months ago, I met a young man 24 years old who was born and raised

in The Bahamas who at the age of 22 was refused citizenship of The Bahamas.

His accent is indistinguishable from any Bahamian’s. He stopped me

in the street and asked me if it was fair for him to be punished because

of what his parents did. He argued that he was not born in The Bahamas

because of his choosing. He took out his passport. It was a

Haitian passport. He claimed he had paid $10,000 to get permanent

residence. He pointed at the Haitian passport and asked me what had

that to do with him. He said he had never been to Haiti in his life,

and then he started to cry. At that point all I could do was to tell

him to hang on that I was certain that it would eventually be solved.

But there are some to whom I have told that story who whose reaction is:

“Too bad. He is Haitian and he should go home to Haiti.”

About

three months ago, I met a young man 24 years old who was born and raised

in The Bahamas who at the age of 22 was refused citizenship of The Bahamas.

His accent is indistinguishable from any Bahamian’s. He stopped me

in the street and asked me if it was fair for him to be punished because

of what his parents did. He argued that he was not born in The Bahamas

because of his choosing. He took out his passport. It was a

Haitian passport. He claimed he had paid $10,000 to get permanent

residence. He pointed at the Haitian passport and asked me what had

that to do with him. He said he had never been to Haiti in his life,

and then he started to cry. At that point all I could do was to tell

him to hang on that I was certain that it would eventually be solved.

But there are some to whom I have told that story who whose reaction is:

“Too bad. He is Haitian and he should go home to Haiti.”

One of the paradoxes of the legal position on citizenship

and the fact that you cannot acquire it by the simple act of birth is the

fact that many Bahamians have for deliberate and other reasons had their

children born in the United States of America, where the simple act of

birth on US soil makes you a US citizen. Bahamians see nothing wrong

with that but they to a large extent seem not to want the same approach

in Bahamian law. The argument is that The Bahamas is too small a country

to withstand citizenship by birth alone.

CARLTON FRANCIS IS SEARCHED

On 24th January 1972, the Nassau Guardian published

the following statement from the Government of The Bahamas:

A statement issued by the Ministry of External Affairs

early Sunday read:

“On Friday, January 21, 1972 the Honourable Carlton E.

Francis and Mrs. Francis left Nassau on a private trip to Miami on Pan

American Airways flight 410 and arrived in Miami about 6:30 p.m.

On arrival in Miami Mr. And Mrs. Francis passed through the United States

Immigration Authorities without incident. At the United States Customs

checkpoint they surrendered their Customs Declaration in the usual manner

and were cleared through. On their way to the exit from the Custom

Hall they were stopped by Mr. J. E. Penner, a United States Customs Enforcement

Officer and Mr. A. Hoffman a United States Special Agent who requested

the Minister to show him his passport and accompany him to some place where

a personal search could be conducted.

“Mr. Francis accompanied the men but refused to

be searched. He requested information as to why a personal search

of himself was being requested; he pointed out that he had already cleared

customs in the normal manner; and he demanded the usual courtesies as a

Minister of the Bahamas Government.

“The United States officers asked Mr. Francis to

prove that he was a Minister. In addition to the forms of identification

offered to but refused by the Officers as unsatisfactory, Mr. Francis telephoned

British Vice Consul, Mr. R. J. Barkley and requested him to come to the

airport, Mr. Francis, however, was not allowed to make a long distance

call to Nassau.

“While waiting for the Vice Consul to arrive, the

United States Officers informed Mr. Francis that there was a protrusion

from his trousers and that they had apprehended several persons carrying

contraband and prohibited goods in their crotch. The Minister explained

the cause of the protrusion but this too was unacceptable to the Officers.

“The Vice Consul arrived, identified Mr. Francis

and reinforced the identification with a listing from the Bahamas Official

Gazette. Even this was not sufficient to satisfy the United States

Officers who insisted on the search taking place.

“After some two hours had gone by, the senior Agent

informed Mr. Francis that Washington had to be contacted for the final

word. Later the Agent claimed that word had indeed come from Washington

that the search had to be made. At the request of the British Vice

Consul, who Mr. Francis had asked to call Washington and Nassau, the United

States Officers promised that they would await his return to the room before

proceeding with the search.

“While the Vice Consul was out of the room, however,

two officers held the Minister, each one twisting an arm behind his back.

Another loosened the Minister’s trousers. The search was completed

about 10:30 p.m.

“The Vice Consul returned to the room after the

search had been completed. He apologized for not having returned

to personally tell the Minister the results of his telephone calls but

admitted having given the information to the United States Customs Agent

Mr. Hoffman.

“Some time after 11:00 p.m. the Minister enquired

why he was still being detained. He was then informed that as there

appeared to have been no customs violation on his part he was free to leave.

The Minister did not in fact leave the airport until after 1:00 a.m. the

next morning.”

On the night of those events, I was in Nassau at

home on break from University in the United States working with J. Vibart

Wills at what was then the Public Affairs Division of The Bahamas Information

Services. What had been done to the Minister had caused quite a stir

and in the debates of the day, it was argued that this illegal search was

not something that could have happened if The Bahamas was an independent

country. We would be able to defend ourselves and the immunity that

would have been afforded to a Bahamian minister would have protected him

from a search to which he did not agree.

And that story goes through my mind each time a

Minister of The Bahamas Government who by force of circumstances must travel

through airports are almost strip-searched passing through on their way

to their final destinations. Ministers of The Bahamas Government

passing through airports have been made to take off their belts, their

shoes, their watches and chains and rings and to have their luggage opened

and rifled because of the measures to protect against terrorism.

The same practice happens to Bahamian Ministers traveling in their own

country.

The constitution of The Bahamas prohibits the mandatory

search of a person, except with his consent. It also allows the arrest

or detention or the search of a person in cases where there is a reasonable

suspicion of his or her having committed an offence, of being about to

commit one or in the process of committing one. None of these criteria

apply to Ministers of the Government passing through airports. One

remembers a successful case by Fred Smith, the Freeport attorney, who was

stopped at a roadblock in Freeport and challenged the legality of the process

in the courts. The then Chief Justice Telford Georges ruled that

you cannot have a reasonable suspicion of everyone stopped in the roadblock;

that in itself is unreasonable. No doubt there are some who would

argue that the exception in the constitution ‘in the interest of public

safety’ applies at airports in that there is a real likelihood that if

the searches did not take place on everyone there might be an incident

of terror on the plane and that risks outweigh any constitutional concerns

about unreasonable searches.

But I recall the words of a former Governor of the

state of Oklahoma in the United States who said recently that his country

was not serious on safety at airports when it was searching 83 year old

ladies and making them take their shoes off.

Clearly sovereignty and independence have not brought

those protections. And it begs the question of what does sovereignty

and independence mean. And what does being Bahamian mean as opposed

to being the national of another country? What protection does The

Bahamas government offer to citizens of The Bahamas both at home and abroad?

What protection can it afford? What protection should it afford?

These are not just casual questions for a Minister

of Foreign Affairs since it is that Minister’s responsibility to provide

consular assistance to Bahamians abroad. Central to what a Foreign

Minister does is standing up for the people that define themselves and

have been accepted in that definition by the world as Bahamians.

That Foreign Minister as an agent of the Government of The Bahamas seeks

to offer protections to Bahamian citizens abroad. It is certainly

not a military protection. It is a protection under the rule of law.

Yet some would argue that what is happening around the world where power

appears to be the only fact that counts is that moral protection, that

of the rule of law is in fact being eroded and means little.

And in fact there are some in the country who would

argue that there is no point to independence and sovereignty if the result

is poverty and hunger. Indeed in many of the arguments that have

been made on the subject by editorial writers in The Bahamas it has been

said that there is no point to a Foreign Minister of The Bahamas seeking

to publicly defend The Bahamas in the face of a superior power. The

argument (and I am paraphrasing here) appears to be that because we are

small, not rich and an unimportant player in the world, we ought to keep

our heads down as a country and do exactly as we are told to do by those

who are the bigger players in the world.

While this finds some resonance with many Bahamians,

there are equally fierce arguments on the other side that the country’s

sovereignty means something and it ought to be defended vigorously no matter

the price. The Government has to weigh carefully both opinions and

most government’s - this Government included - has chosen to defend the

country’s integrity but not to pick unnecessary fights because such fights

do not serve the larger interests of the country.

The matter is a serious one that Bahamian Governments

have to face. This Government, for example, will shortly be called

upon to make a decision with regard to whether or not the proposals to

supply natural gas through underwater pipelines to Florida should be allowed.

Some would argue that if the powerful commercial interests in another country

demand this, there is no way The Bahamas can say no, even if we find out

that the facilities will be detrimental to the environment of The Bahamas.

But I believe and I take this point to the public

policy in which I am involved that this country has survived effectively

as a separate jurisdiction for almost four centuries and that we have the

skill to continue to survive as a separate jurisdiction; that we have a

way of life that is different from any other and which I think ought to

be defended. That defence must come whether it is against a

threat from military might and wealth or from poor migrants threatening

to swamp our shores.

I have argued that the separateness of this jurisdiction,

our independence has beyond a social or cultural component to it.

It also has an economic component. The success of this country’s

economy is in fact predicated on the separateness of this jurisdiction

and the laws which protect privacy and private wealth. There is a

tourist sector that in fact thrives because this is a foreign country in

the eyes of those who come here; a foreign country that has a different

way of life. The policies of successive administrations to defend

our laws and our way of life have produced a good way of life for the people

of this country. There is therefore a need to defend that way of

life. This is uppermost in the mind of any Foreign Minister of The

Bahamas.

In 1897, the Anglican Church of St. Agnes

was established in Miami, Florida. The church is still there today.

It has some 3000 members, most of them of Bahamian descent. The church

was founded by Bahamians who had emigrated to South Florida seeking opportunity

and a better way of life. Just as the Haitians formed an inexpensive

labour pool for us, we formed such a pool for many cities in the United

States. And it appears that the group that emigrated was a relatively

skilled group.

Canon Richard Marquess Barry who is a descendant

of Eleuthera is the rector of St. Agnes in Miami today. And he tells

the story of the church’s founding when an English priest was visiting

a white family in Miami and he heard the black washerwoman singing the

hymn ‘The Church is One Foundation’. The priest knew that this was

an Anglican hymn, not normally associated with black people in the United

States. He inquired of the woman where she had learned the hymn.

She told him that she was member of St. Agnes Church in Nassau but that

there was no place of worship for blacks who were Anglicans in Miami, having

regard to segregation in the south. The conversation led to the founding

of the church. And all of its rectors except a few have been connected

in some way to The Bahamas by descent or birth.

Today, as Canon Barry prepares to retire, he has

told the congregation that he hopes that whomever they choose, that person

ought to be able to cook and eat peas and rice.

If you attended St. Agnes in Miami today, you would

find a church with a service that very much resembles and feels like the

service in St. Agnes in Nassau. The interesting thing about this

for me is that the sense of what is Bahamian for these Bahamians overseas

has been defined in terms of the Anglican Church that is really English.

But in embracing the Anglican Church abroad, they were able to feel close

to their roots at home in The Bahamas.

It should be pointed out that it is because of stories

like the one of St. Agnes, Miami, the settlement of Bahamians at Key West,

Florida and the fact that we are the only grits eating population in the

Caribbean, having brought the food with the slaves who came from the Carolinas

after the war of 1776, that The Bahamas is in fact a sub culture of the

culture of the United States of America.

The stories also say something about us as a people

beyond the legal concept of who we are. And I have so far throughout

this discourse sought to distinguish between the legal concept of who is

Bahamian and the social or cultural concept. And I would argue here

that we must try as we move forward to ensure that the legal definition

of who is a Bahamian comes as close as possible to the social or cultural

definition of who is a Bahamian. My argument is that this is in the

best interest of our country as we move forward in this century.

It is in my view in the best interests of the sovereignty and independence

of this country to be inclusive in our legal definition as Bahamians, not

exclusive, in the same way that for example the state of Israel or the

United Kingdom is. I would be interested to hear the responses on

this.

The difficulty is that social and cultural definitions tend to change over

time, so they have to be rooted in some fixed concepts. One of them

I believe should be birth, the other ought to be ancestry but I do not

believe that these (birth and ancestry) ought to be necessarily joined

together. They can be separate legal bases for the claim of citizenship.

In other words, you ought to get to Bahamian citizenship either by birth

or by ancestry, whether married or not and whether through the male or

female lines.

The difficulty is that social and cultural definitions tend to change over

time, so they have to be rooted in some fixed concepts. One of them

I believe should be birth, the other ought to be ancestry but I do not

believe that these (birth and ancestry) ought to be necessarily joined

together. They can be separate legal bases for the claim of citizenship.

In other words, you ought to get to Bahamian citizenship either by birth

or by ancestry, whether married or not and whether through the male or

female lines.

Indeed one of the other causes of confusion in the

changing Bahamas where 70 per cent of the births are out of wedlock, is

the child of a Bahamian father who is born out of wedlock cannot

claim citizenship of The Bahamas unless that child was actually born in

the Bahamas. If he were born in The Bahamas he can apply at age 18,

which means he does not get it automatically. If he were born abroad,

he cannot qualify for it at all. We enter here into the realm of

morality and whether or not the children of unions outside the bonds of

marriage should be recognized at all as legitimate or whether we ought

to continue to ignore the realities on the ground and in our discussions

after this that is something I would like to hear more about.

And so beside births, what other elements are there

involved in the social or cultural definition of who is Bahamian?

First there is ethnicity, then there is place of national origin, then

there are class elements. I would wish to discuss each of these in

turn and then seek to hear your views in the discussion period afterward.

First race and ethnicity: Colin Hughes has

written what is perhaps the most authoritative study of the subject in

his book Race and Politics in The Bahamas, now out of print. The

work was published in 1977 and it seeks to trace the effect of race as

the most important cleavage in the politics of The Bahamas. The Bahamas

has since the politics of the 20th century largely defined itself as a

black nation. Mr. Hughes seems to argue that race is the most

important political cleavage in The Bahamas. It is clear from recent

public discussions about one of the candidates for political leadership

that it still enters the discussion but last year’s referendum and general

election was thought by many to be the first time where race played less

of an issue than the issues themselves. It seemed that the races

crossed the traditional party lines in an unusual alliance. But traditionally,

when one thinks of a Bahamian, most people including Bahamians would think

of a person of African descent.

This was reinforced in the events of 1942 and the

Burma Road Riots and in the popular song of the day, which included the

line: “Burma Road declare war on the conchy joe”. It was further

reinforced by the proclaiming of Majority Rule in 1967 on 10th January

when Sir Lynden assumed the office of Premier. Sir Lynden’s Government

replaced the Bay Street, all white oligarchy that controlled the country

up to that day.

In later years, in a politically correct attempt

to be all inclusive, some pundits have suggested that Majority Rule Day

be adapted to include a wider meaning, that of all Bahamians experiencing

for the first time the full effects of one man, one vote, since there was

in 1967 universal adult suffrage and single member constituencies for the

first time. But most people still think of Majority Rule day as the

day that marked the ascendancy of the African descendants in The Bahamas

to Government.

My own thought is that the more inclusive definition is

more compelling in today’s Bahamas but the historic position should not

be dismissed.

The interesting thing is that if one were to examine

ethnicity in its purest sense, one would discover that the situation is

not as clear cut as all that. The question can be asked within the

Bahamian context - and this is not exclusive to The Bahamas - who is white

and who is black? And there are clear demarcations in both communities

in The Bahamas, notwithstanding the appearance or what used to be on the

birth certificate.

For example, when I was born in 1953, my birth certificate

has on it the designations of race. ‘A’ for African, ‘E’ for European

and ‘M’ for mixed. Cyril Stevenson who was the Editor of the PLP's

newspaper The Herald used this to some effect when he discovered that a

Parliamentarian now deceased who would generally be considered white had

a birth certificate that had ‘M’ or mixed on it. The Herald proclaimed

in one of its headlines words to the effect that the Parliamentarian was

a black man. Presumably that was the ultimate political insult of

the day for anyone who thought of themselves as white and lived in a white

world.

Colin Hughes, whose last name is found in the law

firm McKinney Bancroft and Hughes, laid out certain classifications in

his book and sought to define how race played itself out in terms of the

definitions in The Bahamas.

He describes several categories. One is phenotypical

colour; that is the one we all know. In other words, if you look

at me, you will see an African Bahamian and describe me as a black man.

If you looked at Brent Symonette, you would say he is a white man. But

Mr. Hughes also describes other kinds of colour - associational colour,

cultural colour. And it is these latter categories that explain in

The Bahamas a situation, which is not as simple as black and white.

So one finds that in The Bahamas, people of mixed ancestry who were light

skinned could often cling to one side or the other, and typically they

chose because of the power relationships in the society to be white.

This is separate from the question of biracialism,

which arises today in the international arena as other countries grapple

with definitions of race.

But historically in The Bahamas, people of mixed

ancestry who were light skinned, as if to reinforce their choice to be

white, enforced a more rigid segregation than the whites themselves, even

for example in several well known cases shunning darker brothers and sisters

in the same families. The late C.W.F. Bethell, the former Government

Minister in the UBP, for example, whose ancestry was clearly European admitted

once in an interview with The Tribune that his father had several children

born out of wedlock with black women who could not be patrons at the Savoy

because of their colour. He said he regretted it.

And then there was the famous candy store, on the

site of what is now a popular restaurant in town, which was owned by a

mixed family but one that did not allow blacks to be served. And

it is still a point of awkwardness today when you speak to many of the

families in that category when it comes to what colour they are.

The matter is so sensitive that I will not call the names of the families

even today. They tend to describe themselves not as white, because

they believe they will be challenged by the black community or rejected

by the white community but they at best describe themselves as people of

colour or as I heard one family describe themselves as “not being black”…

There are even some who are dark skinned that fall

into that category. The fact is that they grew up in the neighborhoods

in New Providence that were largely segregated, and lived amongst the white

people. They had the habits of white Bahamians and hung out in spots

that mainly white Bahamians did, so notwithstanding their ethnic group

or heritage they by reason of association and choice were white people.

If you examine the white community, of course, you

have two historic bodies and in the twentieth century perhaps a third.

One is descendants of the group that originally settled these islands with

their small group of slaves. Those whites were called “Conchs” and

no doubt that expression is the beginning of today’s “Conchy Joe”

Then Michael Craton points out with Gail Saunders

that following the revolution in the United States in 1776, loyalists and

their slaves came to The Bahamas. The loyalists revolutionized life

in the islands. Reorganized the economy, and brought a different

ethnic mix to the country. For the first time in the history of the

islands, it appears that the black population outnumbered the white population.

Thus began what in hindsight was the inexorable march toward the ascendancy

of the African as the primary political force in the country.

But notwithstanding the numbers, the power equation

was clearly dominated by Europe. The language, the formal structures,

the Government, the church, the technology were all dominated by Europe.

There was such a strong overlay that some called it suppression of that

which was African but there was always the undercurrent of Africa that

only now finds its fullest expression in the society.

So the question might still be asked today when

one talks about a Bahamian under both the legal and the social and cultural

definitions, what ethnic group and their cultural influences are we talking

about—white or black? And further, when we talk about Bahamians,

it would seem the answer is that we are a heterogeneous or diverse society,

and the success of the country is the acceptance of that heterogeneity

– because in many ways the white Bahamas is a different one from the black

Bahamas. Although, it is argued that in recent years, as the degree

of the differential of wealth has decreased and colour no longer marks

exclusively social class, the distinction between the two Bahamases has

markedly declined.

Within the black community, the historic African

community appears to be made up of the blacks who are descendants of the

slaves brought with the loyalists but what appears more and more to be

true and this will require some study is the fact that in the late nineteenth

century following the revolution in Haiti, and the twentieth century with

the demand for labour in the public service and the skilled trades, the

Black populations swelled as a result of immigration from Haiti and the

West Indies. It is in large part that latter group, which eventually

defined in a legal sense what a Bahamian is today. They framed the

nation we have today, and they ensured whether consciously or not that

when Bahamian was defined in a legal sense it included them – born in The

Bahamas with at least one parent who was Bahamian, and in most of those

cases that was the mother.

One must also remember that Sean McWeeney writes

in his essay on the subject that Stephen Dillette, the first Black Member

of Parliament, was a French African. In the language of his day that

translates today to mean he was Haitian and there are several families

with similar origins now prominent and unquestioned in The Bahamas.

I now turn to the question of National Origin.

One of the ways that you can attempt to insult the ‘real’ Bahamian or the

‘true’ Bahamian is to call someone a Haitian. To a lesser extent,

calling someone Jamaican has the same effect. It is easy in the lexicon

of the day to accuse one family or the next of not being Bahamian.

Indeed at one of the civil society consults that we had at the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs when I asked the question about the nature of Bahamianess,

Geoffrey Brown, a white Bahamian, answered that his family had been in

The Bahamas for seven generations. Not many families can boast of

that in this country. One black family that can is the Forbes family

in Driggs Hill, Andros who claim that their ancestors have been in The

Bahamas since 1790.

The fact is that we have all come from somewhere

else. The indigenous inhabitants of the island were all but wiped

out within fifty years of the arrival of Columbus and none of us resembles

them today. So it is true that all of us came here on a boat, more

recently on a plane and it is just a question of how long ago we came.

If you take Mr. Brown’s comment, you become Bahamian

then not just by your being born here, not by your father or mother being

a Bahamian citizen but also by the length of time that your family has

been in the country. And so what we see is an assertion of a greater

claim to Bahamianess if your family arrived before the 20th century.

So it is doubly interesting that those who defined what Bahamian is in

a legal sense were in fact – in many cases -the first generation of their

families born in The Bahamas, their ancestors having come to The Bahamas

within the last one hundred years. That was sufficient for their

purposes to be included as Bahamian.

Now could that be because as I have posited before

in this piece that they were the real founders and crafters of the state

we now know as the Commonwealth of The Bahamas? During the 20th Century,

men and women from Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Cuba, Greece,

Guyana, Turks and Caicos Islands, Britain, Canada, Ireland, the United

States and most certainly Haiti migrated to The Bahamas mated and intermarried

with the Bahamians they met here and became Bahamians themselves.

In fact, it is often argued that without the votes

and the economic support of the sons and daughters of the West Indians

who came here, and the émigrés themselves, The Bahamas would

not have had the political changes that came to the country.

Someone ought to do a census of various countries

of national origin that had their citizens settle here and their descendants.

It was once said by a Trinidadian that Bahamians sounded to him like Barbadians

with an American accent.

I would also commend to you the book by Dawn Marshall,

‘The Haitian Problem’, together with Sean McWeeney’s piece on Haitian migration

in the 19th century. If you travel to Port-au-Prince, and look at

the people there, they bear an uncanny physical resemblance to the masses

of people you find in The Bahamas, just the physical look of them, or phenotypical

colour in the language of the ethnicologists.

It is argued that many of the names that we accept as

English names are in fact Anglicized French or Creole names that have come

over the centuries to be Bahamian. That too is something that ought

to be traced and studied.

The end result appears to be that The Bahamas and

Bahamian as they are defined today are very much a country and a people

of immigration. The country developed on the strength of immigration,

despite the antipathy to immigrants in the country. As the economy

continued to grow, the civil service, the skilled trades, the common labourers,

the professional classes were all augmented by labour from the southern

Caribbean. The nation then is replete with the descendants of those

nationalities. It should be instructive to the Government as it plans

the public policy of our new economic and political relationships in the

Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas

(FTAA).

The continued immigration into the country from

the south has a number of effects. One is that it keeps the population

black. We have no census data on the ethnic make up of the country

but the impression is that net emigration; that is outwards, is proportionally

more significant in the white population that maintains its ethnic integrity

by marrying whites from abroad and then moving abroad. And there

is a relatively larger immigration; that is an inflow to the country, amongst

the black populations of the Caribbean and more particularly Haiti.

We need to have the data on this.

I now turn to the question of social class. The

social construct that Michael Craton and Gail Saunders have written about

since the time that this country was settled by the English had the whites

from England that ran the colony and represented the imperial power at

the top with whites of Bahamian ancestry next followed by the mulattoes

or brown skins with the great masses of black people at the bottom.

While this has changed somewhat in the last fifty years, that construct

still applies. The response of most people today would still put

most whites in The Bahamas in the upper classes and relatively more wealthy

than blacks as a whole. When I grew up in New Providence it was said

to be conventional wisdom that unlike Jamaica we did not have a rigid class

structure in The Bahamas but we did have racial segregation. They

said what Jamaica had was not segregation but a rigid class structure.

In fact both in both countries seem to the causal observer to coincide.

Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison once said when speaking

of the importance of language that the person who chooses what you call

something is the one who has power. And so when one asks the question

what is The Bahamas and who are Bahamians one has to look also through

the glasses of social class.

All Parliamentarians were asked to attend the funeral

of the late Charles Bethell (generally the whites spelt Bethell with two

ls and the blacks with one), former Minister of the Government and Member

of Parliament. Few of us knew him, most had never even heard about

him but when one read the obituary, it was clear that this was an important

man in The Bahamas up to 1967. If one asked the question who was

Bahamian and what was The Bahamas and you used the construct of Toni Morrison,

you would certainly say that The Bahamas was that of Charles Bethell and

his group, those whites at the top of the society. Their Bahamas

did not resemble in any way The Bahamas in which I grew up.

Their lives were made up of shop keeping, running

the Government, money making, fishing, hunting and foreign vacations back

in their ancestral homes or so it appears. This was completely alien

to anything in my experience and something that as an African Bahamian

living in New Providence, I could only read about in newspapers.

We lived in the same country but our countries were in fact different.

While writing this I added African Bahamians living in New Providence because

in talking to many of my compatriots in the family islands, they do have

the fishing and hunting experience.

Throughout the 20th century, with the political

revolution that took place and the inclusion of blacks in the upper echelons

of the Government and increasingly in the economy, the complexion of the

upper classes changed in the country, the children of immigrants became

the leaders in the country. If you accept what Toni Morrison has

said this phenomenon must necessarily redefine what being Bahamian means.

Many Bahamians seem to be sensitive about the development

of class distinctions in the society. And we still argue that we

do not have a rigid social class structure in this country, so that social

mobility is quite fluid in The Bahamas. The experience of the generation

to which I belong is that it is possible in one generation

to move from one class to another. Indeed within our own time, it

is possible to move from one class to another. From a public policy

point of view this is a continued desirable objective. And it seems

to me that when we define this question of who is Bahamian, what being

Bahamian means and in fact ask the more profound question whose Bahamas

is it anyway; we ought to bear that objective in mind.

The interesting thing about this is that the social

mobility has also applied to immigrant families as well. Although

anecdotally you hear some resentment from the Bahamian by birth who argues

that the well educated immigrants coming into the country are able to marry

into Bahamian families and get right to the top of the ladder, this has

not yet reached the point where serious public policy attention has been

paid to it. As a Minister of the Government one inevitably hears

this pressure coming from Bahamians to be applied through a work permit

policy that seeks to protect Bahamianization and also chauvinistic in that

the reason often given is to protect our women. Of course Bahamianization

continues to be an objective of the Government.

This then sets the basis for our discussions this

evening. In summary, we have looked at the various definitions of

Bahamian, including racial, national origin and class components.

We have looked at the legal definitions. We have argued that perhaps

it is time to change the legal definition so that it more accurately reflects

the social and cultural notions of what is Bahamian and is more inclusive

than exclusive. We have argued in favour of continued social mobility

in the society. We have argued that the Bahamian way of life is deserving

of protection and defence, while we recognize it as a dynamic state not

static. We have argued that The Bahamas is a diverse and heterogeneous

society that quite apart from a legal definition encompasses many different

races, shades, national origin and cultures that is continuing to evolve.

This dialogue with you will be instructive for me

as the Minister of Foreign Affairs and indeed as Minister for the Public

Service as I seek to assist in the development of public policy with regard

to our country. I look forward to the dialogue with you.

Thank you very much indeed.

- end -

I wish to say at the outset what an honour it is for me to have been asked

to deliver this distinguished lecture. I express my thanks to the

Sir Lynden O. Pindling Foundation in particular the widow of Sir Lynden,

Lady Marguerite Pindling. I wish also to thank the Chairman, Council

and President of the College of The Bahamas for this opportunity.

I would like in particular to thank my friend Felix Bethel, now a lecturer

in politics at the College of The Bahamas and head of the Social Science

Division of the College. We have both come a long way since those

days when we used to share in the purchase price of the Sunday New York

Times, almost thirty years ago.

I wish to say at the outset what an honour it is for me to have been asked

to deliver this distinguished lecture. I express my thanks to the

Sir Lynden O. Pindling Foundation in particular the widow of Sir Lynden,

Lady Marguerite Pindling. I wish also to thank the Chairman, Council

and President of the College of The Bahamas for this opportunity.

I would like in particular to thank my friend Felix Bethel, now a lecturer

in politics at the College of The Bahamas and head of the Social Science

Division of the College. We have both come a long way since those

days when we used to share in the purchase price of the Sunday New York

Times, almost thirty years ago.

The Hon. Darrell Rolle was then the Minister for Transport and one of the

members of the delegation negotiating the Independence of The Bahamas with

the British. Somehow during the talks, I met up with Mr. Rolle

and happened to take a taxi ride with him to a train station from the Dorchester

Hotel while he went on to Lancaster House where the talks were coming to

an end. I remember him saying to me that the Government had put forward

a proposal that would effectively prevent the children of illegal immigrants

from claiming the citizenship of the new state to be known as the Commonwealth

of The Bahamas.

The Hon. Darrell Rolle was then the Minister for Transport and one of the

members of the delegation negotiating the Independence of The Bahamas with

the British. Somehow during the talks, I met up with Mr. Rolle

and happened to take a taxi ride with him to a train station from the Dorchester

Hotel while he went on to Lancaster House where the talks were coming to

an end. I remember him saying to me that the Government had put forward

a proposal that would effectively prevent the children of illegal immigrants

from claiming the citizenship of the new state to be known as the Commonwealth

of The Bahamas.

About

three months ago, I met a young man 24 years old who was born and raised

in The Bahamas who at the age of 22 was refused citizenship of The Bahamas.

His accent is indistinguishable from any Bahamian’s. He stopped me

in the street and asked me if it was fair for him to be punished because

of what his parents did. He argued that he was not born in The Bahamas

because of his choosing. He took out his passport. It was a

Haitian passport. He claimed he had paid $10,000 to get permanent

residence. He pointed at the Haitian passport and asked me what had

that to do with him. He said he had never been to Haiti in his life,

and then he started to cry. At that point all I could do was to tell

him to hang on that I was certain that it would eventually be solved.

But there are some to whom I have told that story who whose reaction is:

“Too bad. He is Haitian and he should go home to Haiti.”

About

three months ago, I met a young man 24 years old who was born and raised

in The Bahamas who at the age of 22 was refused citizenship of The Bahamas.

His accent is indistinguishable from any Bahamian’s. He stopped me

in the street and asked me if it was fair for him to be punished because

of what his parents did. He argued that he was not born in The Bahamas

because of his choosing. He took out his passport. It was a

Haitian passport. He claimed he had paid $10,000 to get permanent

residence. He pointed at the Haitian passport and asked me what had

that to do with him. He said he had never been to Haiti in his life,

and then he started to cry. At that point all I could do was to tell

him to hang on that I was certain that it would eventually be solved.

But there are some to whom I have told that story who whose reaction is:

“Too bad. He is Haitian and he should go home to Haiti.”

The difficulty is that social and cultural definitions tend to change over

time, so they have to be rooted in some fixed concepts. One of them

I believe should be birth, the other ought to be ancestry but I do not

believe that these (birth and ancestry) ought to be necessarily joined

together. They can be separate legal bases for the claim of citizenship.

In other words, you ought to get to Bahamian citizenship either by birth

or by ancestry, whether married or not and whether through the male or

female lines.

The difficulty is that social and cultural definitions tend to change over

time, so they have to be rooted in some fixed concepts. One of them

I believe should be birth, the other ought to be ancestry but I do not

believe that these (birth and ancestry) ought to be necessarily joined

together. They can be separate legal bases for the claim of citizenship.

In other words, you ought to get to Bahamian citizenship either by birth

or by ancestry, whether married or not and whether through the male or

female lines.